Funding and Responding to Climate Risks

As the risks of flooding increase, and extreme weather events become more common, questions arise about where funding should be directed, how it should be managed between disaster responsiveness and pre-disaster adaptation, and the governance levels from which it can be accessed. Communities on the coasts and inland face risk, in terms of properties, infrastructure and livelihoods. While municipalities like Boston conduct cost-benefit analysis to prioritize adaptation projects, higher-level Federal funding is often provided immediately post-disaster.

Currently, funding to mitigate and address these risks is reactive, where public entities and individual insurance policyholders receive Federal recovery funding following disasters, rather than funding for protective and adaptive measures. In addition, there are few cohesive regional efforts to plan for climate-related risks.

We explore the distribution and adequacy of Federal funding relative to geography and allocated purpose, as well as the possibility of adaptation-centered planning.

Planning for Adaptation in Boston

In major cities like Boston, billions of dollars of building stock is susceptible to this risk. The City of Boston’s “Climate Ready Boston” initiative currently conceptualizes loss via property values. The calculus of this cost-benefit analysis often leads to the prioritization of high value properties, a well documented phenomenon.

Assessed values for 2018 are shown below:

While cities like Boston are considering adaptation on the basis of local property loss, Federal funding is often directed towards reactive hazard mitigation and disaster relief: This funding is provided at a much larger jurisdictional scale, in reaction to disasters and extreme weather events that affect entire regions. Local governments are often ineligible to apply for Federal money without the involvement of state governments. Therefore, we shift our scale from potential losses at the municipal level to examine funding for the entire region.

Turning to New England

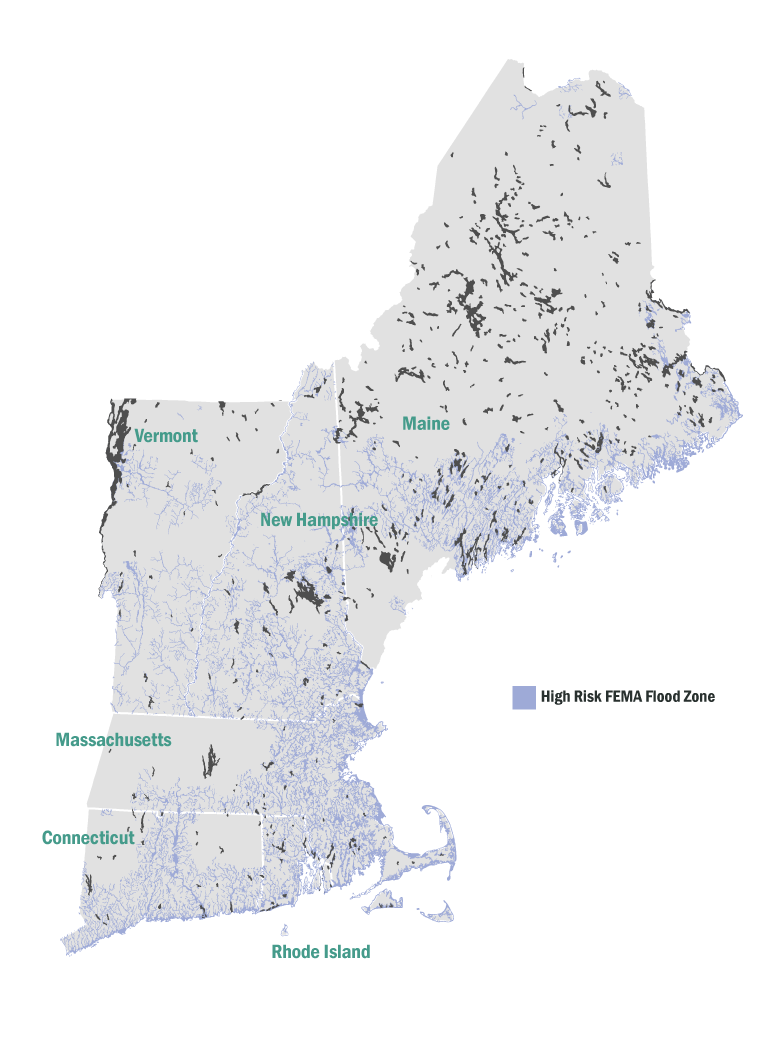

The New England region includes the states of Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Vermont. The map below shows potential flood risk areas on a regional basis based on FEMA’s National Flood Hazard Layer. Considering the region’s high coastline and shoreline exposure, economic contribution, total population, and recent storm events climate risk will be an important factor to consider when planning for the future.

$1,021,856,000,000

Overall GDP

1,607

Number of Municipalities

14,668,879

Total Population:

473 miles

Total ocean coastline

6,130 miles

Total shoreline

States, counties and in some cases, municipalities, receive Federal funding for disaster recovery and hazard mitigation. A large amount of funding comes from HUD as well as FEMA. We show how these are allocated between states and agencies in the diagram below. Specifically, we show funding from FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Assistance Program, Public Assistance Funded Projects, Emergency Management Performance Grant Programs. Of these three programs, a Presidential Disaster Declaration must be in effect for Hazard Mitigation and Public Assistance funds to be made available. We also depict FEMA payouts from the National Flood Insurance Program. For HUD, we show funding from the agency’s disaster recovery grant program. Funding are aggregated from 2008-2018.

FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is the highest funded program of the individual programs shown above. Through this program, individual homeowners and businesses receive payouts on subsidized insurance policies in the event of disaster.

Rather than funding adaptive measures, a large share of Federal funds pictured below go towards payouts to individual homeowners and businesses following disasters. This reactive means of addressing risks treats flooding as an outcome with a given probability, rather than an ever increasing possibility.

Disaster recovery itself is also underfunded. States that receive HUD disaster recovery funding must submit action plans to the Federal agency for review. In these action plans, states detail unmet needs for housing and public infrastructure. The following bar graph shows the value of Federal, state and other grant funding allocated, and the resulting shortfall for the states of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island following Hurricane Sandy and for the state of Vermont, following flooding as a result of Tropical Storm Irene. We adapt this methodology from Keenan (2018).

Relatedly, the National Flood Insurance Program is fiscally unsound, and unable to sustain itself. A recent analysis from the Congressional Budget Office also showed that coastal counties are set to experience severe shortfalls between National Flood Insurance Program premiums and payouts. These shortfalls also demonstrate the need for more adaptive planning, especially in the wake of Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina.

– PBS in partnership with NPR; May 24, 2016

While cities consider adaptive measures based on potential local property losses, it is unclear how these adaptive measures will be funded. Meanwhile, the Federal government provides funding at a larger scale, oftentimes post-disaster. Very little funding is adaptive, and recovery funding is not enough, both for disaster recovery grant programs as well as for the subsidized policies of the National Flood Insurance Program. These problems will only worsen as the risks increase. Federal Funding: Reacting to Climate-Related Disasters

“Investments in adaptation are likely to be among the largest expenditures we make as a region over the next generation, but we have neither a plan or a budget for them.”

Shortfalls Following Disasters in New England

Shortfalls in the National Flood Insurance Program

Note: We provide a graphic depicting the Congressional Budget Office’s Analysis (2017) of the National Flood Insurance Program. Specifically, the graphic is reproduced from the summary located here.

“The flood insurance program was originally intended to be self sustaining — funded through policyholder premiums, not taxpayer dollars — and for much of its history, it was. But the catastrophic hurricanes Katrina in 2005 and Sandy in 2012 caused so much damage that the program could not pay for it all. After Hurricane Katrina, Congress increased FEMA’s borrowing authority from $2 billion to more than $20 billion. They increased it again, to $30 billion, after Hurricane Sandy. The program’s debt to the U.S. Treasury is now $23 billion.”

Conclusions